When Invisible Data Became Visible

Formula 1 is a sport built on invisible margins. Thousandths of a second, microscopic changes in airflow, subtle shifts in temperature — advantages that exist far beyond what the human eye can normally see.

But for a brief moment in 2013, those invisible margins became visible to everyone.

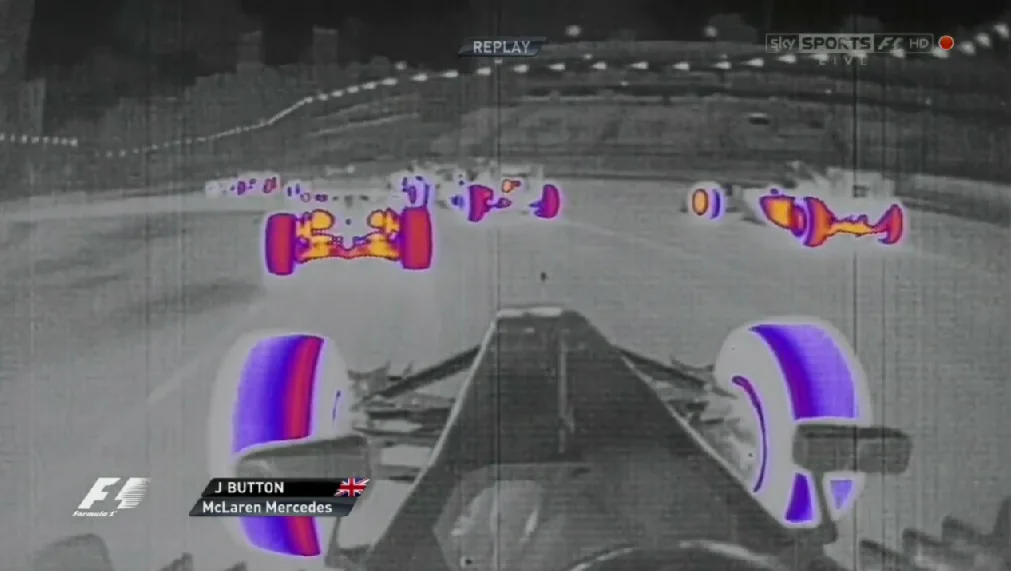

At the 2013 Italian Grand Prix, Formula One Management (FOM) introduced thermal imaging cameras into the live TV broadcast. The goal was simple: entertainment. Glowing brakes, hot tires, dramatic visuals.

What FOM unintentionally created, however, was one of the most powerful competitive intelligence leaks in the history of the sport.

1. The 2013 Incident: A Visual Intelligence Goldmine

Contrary to popular belief, engineers in 2013 were not casually watching thermal images on pit-wall monitors.

Within minutes of the thermal feed going live, teams were:

- Recording the broadcast

- Extracting individual frames

- Running pixel-by-pixel analysis on the footage

By mapping the broadcast’s color spectrum to estimated temperature values — while accounting for emissivity (a material’s efficiency at emitting thermal radiation) — engineers could extract far more than the TV audience realized.

What Teams Could Decode

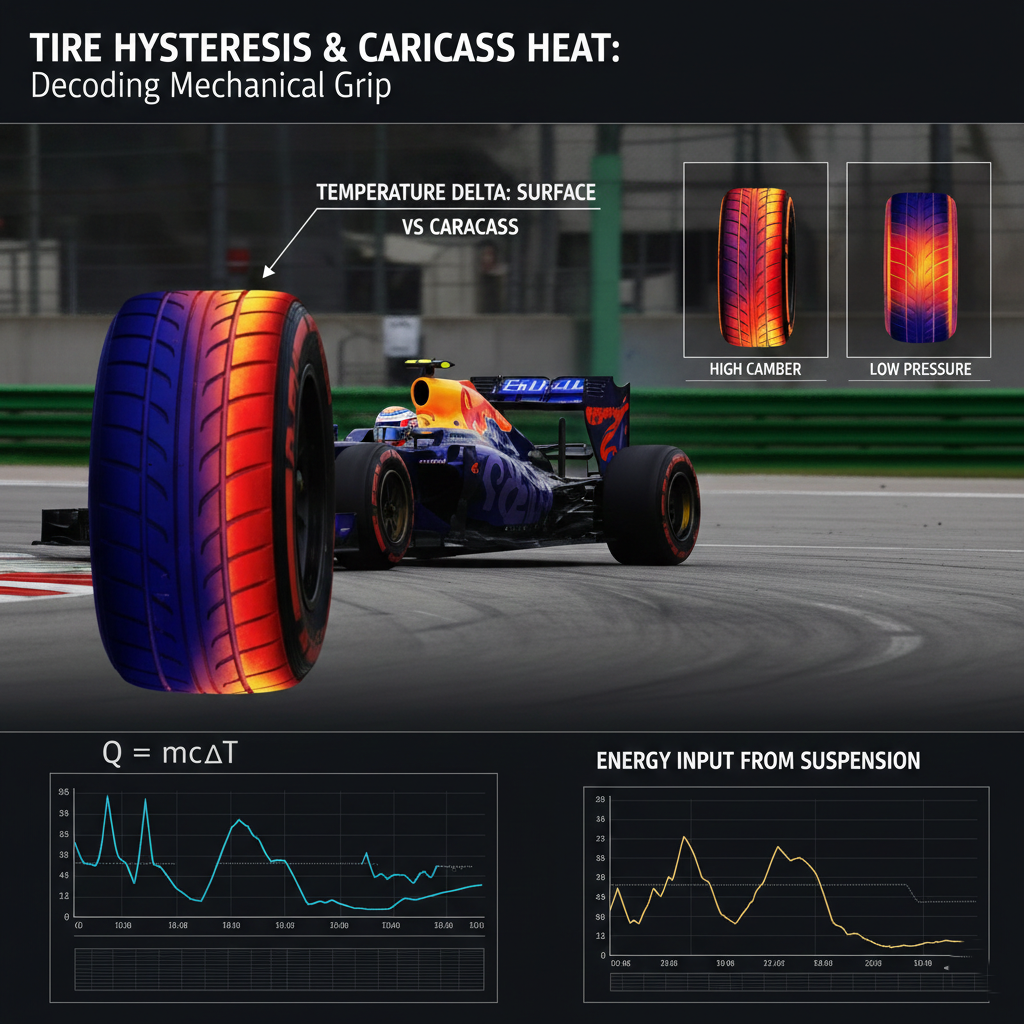

Tire Hysteresis & Carcass Heat

The temperature delta between tire surface and carcass revealed how a rival car was generating mechanical grip, managing energy input, and loading the tire through corners.

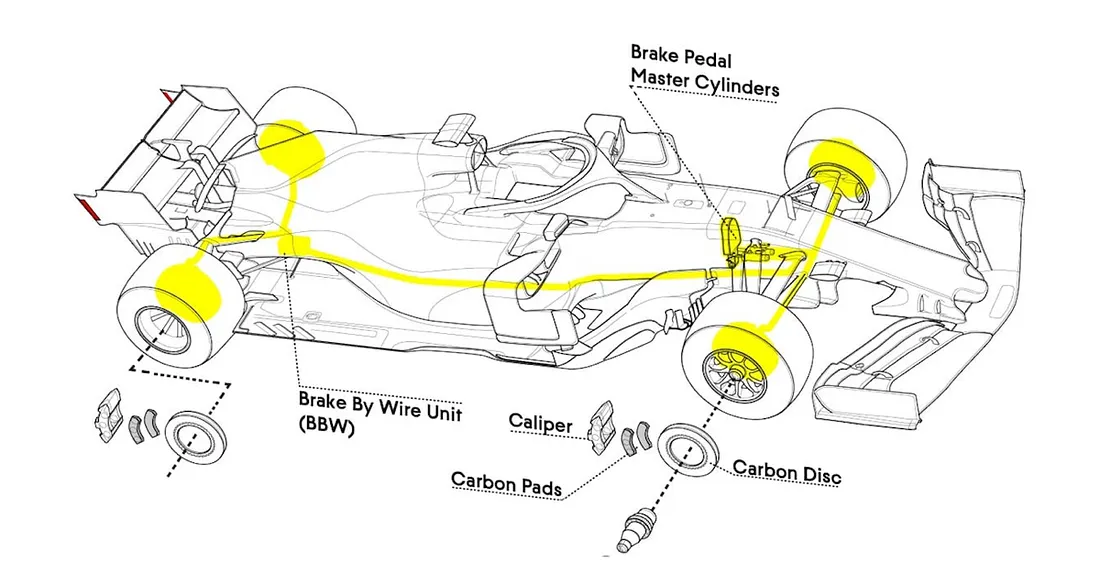

Brake Bias Migration

Thermal “bloom” on front versus rear brake discs exposed real-time brake balance changes under high‑G deceleration — corner by corner.

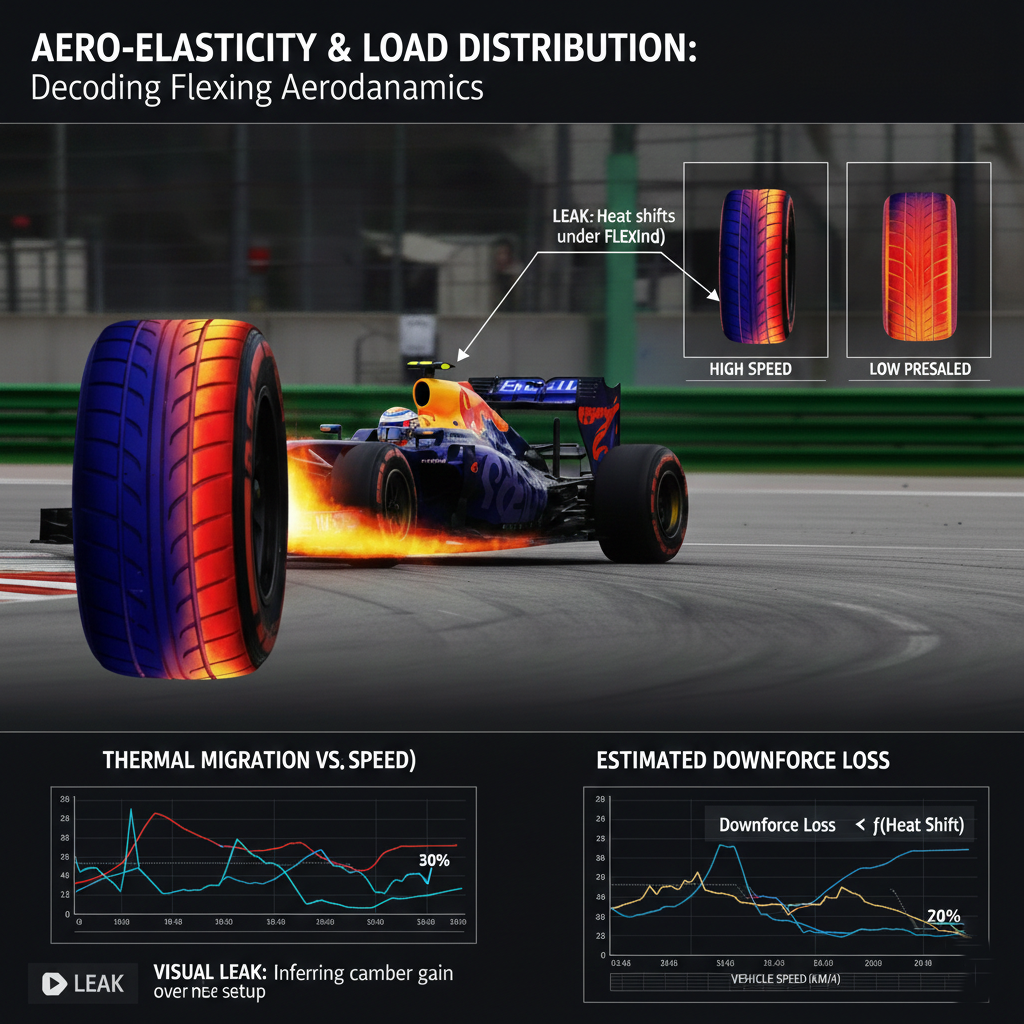

Aero‑Elasticity & Load Distribution

Shifts in heat across the tire tread under load hinted at camber gain, suspension behavior, and even how effectively the floor was sealing at speed.

This wasn’t passive observation.

It was remote reverse‑engineering during a live race.

2. The Science of Thermal Signatures

In thermodynamics, every material exhibits a unique thermal signature — the way it absorbs, stores, and releases heat over time.

When engineers observe a component through a thermal lens, they are not just seeing temperature — they are seeing:

- Material properties

- Internal geometry

- Cooling efficiency

- Energy flow paths

This enables a process known as Inverse Thermal Analysis.

Remote Lab Testing, Trackside

If a rival’s brake ducts appeared hotter but cooled faster than expected, engineers could infer:

- Carbon‑carbon composite density

- Internal vane geometry

- Airflow mass rate through the duct

In effect, teams were performing non‑contact laboratory experiments on competitors — using nothing more than a TV broadcast.

3. 2026: AI, Computer Vision, and the Death of Secrecy

If the 2013 thermal “leak” were to return in 2026, the consequences would not be incremental — they would be exponential.

The key difference is not camera resolution or frame rate.

The difference is the maturity of Artificial Intelligence, computer vision, and data-driven modeling.

In 2013, teams were limited by human interpretation, manual processing, and relatively simple models. In 2026, the entire analysis pipeline can be fully automated, real-time, and predictive.

From Observation to Continuous Learning

Modern AI systems do not treat thermal footage as isolated images. They treat it as time-series data.

By feeding thermal video streams into recurrent architectures such as LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) networks, models can:

- Learn how temperature evolves lap by lap

- Identify repeatable thermal patterns tied to driving style or setup

- Detect early indicators of thermal saturation or degradation

This allows teams to predict performance inflection points — such as tire drop-off — several laps before they become visible to the driver or on standard timing data.

Turning Heat Into Aerodynamic Intelligence

Thermal data is not limited to tires and brakes.

By correlating:

- Heat dissipation rates on straights

- Known vehicle speed from timing data

- Ambient conditions

AI models can estimate airflow efficiency and infer aerodynamic drag behavior.

While not a perfect substitute for wind tunnel data, this approach can narrow a rival’s drag coefficient (Cₙ) into a useful confidence range, providing actionable intelligence with zero physical testing.

Automated Reverse-Engineering at Scale

Modern Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) excel at extracting spatial structure from images.

Applied to thermal footage, they can:

- Convert 2D thermal images into approximate 3D heat maps

- Track how heat migrates across components under load

- Measure cooling rates as a function of time, speed, and airflow

What once required expert intuition can now be done continuously and automatically, across multiple cars, sessions, and race weekends.

The Digital Twin Problem

The most concerning implication is the rise of AI-generated digital twins.

By observing how components retain and shed heat after a run, models can estimate:

- Internal mass distribution

- Material composition

- Thermal capacity and conductivity

Over time, repeated observations allow AI systems to build increasingly accurate approximations of how rival components behave internally — without ever physically inspecting them.

In this context, secrecy no longer fails because information is stolen.

It fails because information is inferred.

Every thermal frame becomes a data point. Every lap improves the model.

In 2026, unrestricted thermal vision would not be a visual feature — it would be a real-time reverse-engineering interface.

4. Why This Crosses the Ultimate Technical Red Line

This is why the FIA is unlikely to ever allow unrestricted thermal imaging to return.

It doesn’t just affect performance — it breaks the economic balance of the sport.

Why invest:

- $50M in simulators

- $100M in wind tunnels

When a $1M AI pipeline can extract usable intelligence directly from a broadcast?

In the 2026 era — where power unit behavior, aerodynamics, and energy recovery are tightly coupled — information leakage becomes performance leakage.

Every photon leaving the car carries data.

And in the age of AI:

If a camera can see it, a competitor can calculate it.

5. The Engineering Lesson: Optimize for What Is Measured — and What Is Visible

One of Formula 1’s oldest truths applies here:

Cars are not optimized for how they are designed — they are optimized for how they are measured.

Thermal imaging exposed parameters teams never intended to share, simply because those parameters became observable.

For engineers and R&D teams, the takeaway is clear:

- Ask what external observers can measure

- Assume competitors are collecting and analyzing public data

- Design systems with observability in mind, not just performance

6. AI Turns Observation Into Prediction

What made the 2013 incident uncomfortable was visibility.

What would make a 2026 version catastrophic is prediction.

Modern AI systems do not just observe states — they learn behaviors.

With enough thermal data, models can:

- Predict component fatigue before failure

- Anticipate performance drop-offs

- Infer internal system architecture from external signals

This shifts competitive intelligence from analysis to forecasting — a far more dangerous capability.

7. Why the FIA Will Likely Never Allow This Again

The FIA’s role is not just sporting fairness, but economic balance.

Unrestricted thermal imaging would:

- Devalue investment in simulation and testing

- Reward data extraction over original R&D

- Create asymmetric advantages for teams with stronger AI capabilities

In a cost-capped era, allowing competitors to reverse-engineer each other via broadcast data would undermine the foundations of the regulations themselves.

8. The Strategic Takeaway

Formula 1 unintentionally demonstrated a future problem every high-tech organization will face:

If your system can be seen, it can be modeled.

In an AI-driven world, secrecy is no longer protected by complexity alone.

It must be protected by:

- Thoughtful exposure

- Controlled observability

- Awareness of what data leaves the system

Final Thoughts

The 2013 thermal camera experiment was not a gimmick.

It was an early warning.

As AI accelerates, the gap between observation and understanding continues to shrink. In Formula 1 — and in engineering at large — competitive advantage will belong to those who understand not just how systems perform, but how they appear to the outside world.

Because in the age of AI:

Every visible signal is a potential data leak.

Written for engineers, R&D leaders, and technologists exploring where physics, data, and competitive strategy collide.